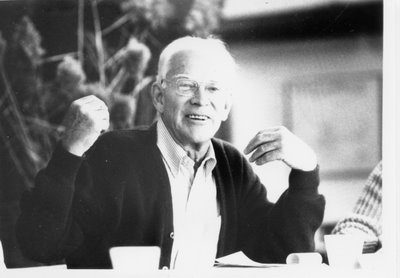

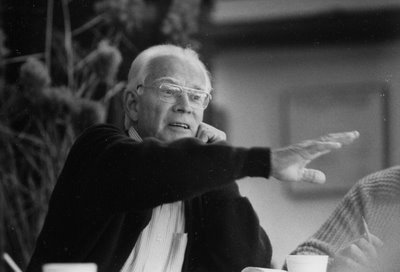

On June 17th, 2005, Americans for UNESCO and the Board on International Scientific Organizations of The National Academies held a celebration of the life of John E. Fobes. Special guests for the event were Federico Mayor Zaragoza (Former Director-General of UNESCO), Harriet M. Fulbright and Harlan Cleveland. The website of Americans for UNESCO was not working when Dr. Fobes died, but we are now taking this opportunity to commemorate his life and his contributions.

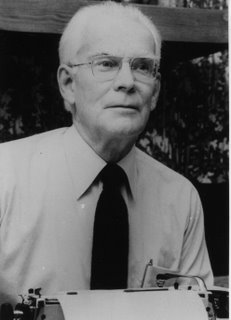

John Edwin Fobes died at his home at the age of 86 on Jan. 20, 2005. A distinguished diplomat, he served as Deputy Director-General of UNESCO, the organization's chief operating officer, from 1971 to 1977, and as Chair of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO on his return from Paris. When the United States withdrew from UNESCO, Jack Fobes immediately founded Americans for the Universality of UNESCO (which subsequently became Americans for UNESCO). From 1985-2002, he headed AUU; through the organization's network and its Newsletter, he virtually single-handedly kept the idea of UNESCO alive in the American mind. In 2002, he assumed the Chair of the Advisory Council of Americans for UNESCO.

He was widely known as a model of global engagement and solidarity. Whether as a United States diplomat or UNESCO official, he was unstintingly dedicated to the cause of peace, human dignity and international understanding. He played an important role in the establishment of the United Nations, and remained an energetic promoter and defender of the Organization’s Charter and global mission. I understand that even shortly before his death, he took the floor at a public meeting to make an impassioned statement in support of the UN’s ideals. Such deeply held commitment was clearly why so many younger people found in him a mentor and teacher, and why his legacy is sure to be felt by future generations.

Kofi Annan

Secretary General of the United Nations

in a letter of condolence to Hazel Fobes

The equal dignity of all the human beings...

They are our commitment, they are our permanent "raison d'être"...

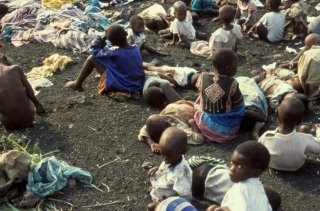

· 50,000 of our brothers and sisters die of hunger every day. We cannot forget it – we have a duty of memory.

· It is this feeling that allows us to dare. "Dare to care" was one of the expressions I took from Jack Fobes in 1988 – dare to share... and to care!

Dear friends, Dear Hazel, family:

I have an immense debt of gratitude to Jack Fobes. He was very helpful, inspiring...

I share your profound grief at the loss of our beloved friend.

------

Jack is my friend. He is not physically present anymore, but he remains present in my everyday life as one who had an important part in forging our attitudes. temper, behavior... As I wrote in a poem to Melina Mercouri: '"The stars lead us long after they have gone dark". Jack was and will ever be a star leading me on my way...

· Jack, a man of vision.

In the watch tower, because what matters is future... to ensure a brighter future to our children...

The succeeding generations: they were the every-day essential thought of Jack Fobes. They deserve to freely write their own future, and we cannot in social, economic, environmental, cultural and ethical terms leave them a legacy of muscle, insolidarity, fear, disorder, confusion, injustice...

He was a great American – he loved his country and its principles – but he was more: he was a world citizen and he had all human beings in his eyes when looking for better sharing, for better care... yes, above all, better sharing! Dare to share! Time, goods, funds, knowledge – sharing better, we can avoid frustration, radicalization, violence, aggression; sharing and listening, we can place the word, the dialog, conciliation where today we have confrontation, the sword, the force...

------

From a speech of Robert Kennedy, I quote: "This world demands the qualities of youth: not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the love of ease."...

Listen to the young people – to work for them is not enough, we must work with them!

The future generations, always in the mind of Jack Fobes: "Education for all... It's time for action"...

------

Life is a mystery. Death is a mystery too. Every single human being is unique, is able to create, to invent.

Jack Fobes: you left, you remain in our mind. You have now immense wings for the endless space. And infinite time. We are still here trying to act as you wanted, in a constant search, with faith and resolve. And freedom. And knowing that if there is no wind, we must row.

"Never gloat" was his motto; he never sought nor accepted glory. I remember his reluctance when UNESCO awarded to him the Nehru Gold Medal. Now, I understand Jack's grace: now, only now, he is with a force so strong he must accept his glory. Jack, I truly believe, “has gone to Glory”.

A presentation by Richard Nobbe

On The Occasion of The June 17, 2005 Memorial Service

Much has been written and said about John E. Fobes the scholar, diplomat, international civil servant, visionary - and unabashedly pro-UN activist. But who was Jack Fobes the Man?

I don't profess to have mastered the subject because the truth of the matter is Jack was a very private and complex person. But what I have done is to assemble a collage of images based on anecdotal remembrances which will provide you a glimpse into his character.

His wife Hazel tells me he was raised by a protective mother and a prudish intellectual maiden aunt on his mother's side and by two aunts on his father's side (the wealthier side of the family) who inculcated in him a love of archaeology and geography.

Jack was a train buff. As a youth, he used to slip away to visit the train yards to study and master the number wheels that gave a locomotive its name. He also had a valuable collection of "Lionel" trains with belching vapor, blinking lights, and piercing whistles. His first job upon graduating cum laude from college was as Director of Train Tours through the Canadian Rockies down the west coast into Mexico. In fact, it was on one of those trips that he met his wife Hazel. According to her, it was an instant whirlwind romance, love at first sight, ever constant, ever true. Today, as we commemorate Jack's life, the rear bumper tag on his car still reads, "I'd rather be riding a train." Toot! Toot!

Jack was an ardent lover of classical music. He could identity compositions and composers by listening to the music. As a youth. he participated regularly in meetings of musical groups established throughout the country by the late Leonard Bernstein to foster appreciation on the subject. And he won several prizes.

Jack professed not to be interested in sports. He was in fact a great athlete and excelled in track and swimming, having served as captain of the varsity swimming team at Northwestern University. His daughter informs me she is alive because of his prowess in swimming. During his assignment to India, the family went to the ocean one day and she got caught up m a riptide which carried her out to sea. Sensing danger, Jack raced to the water's edge, hurtled the waves, and rescued her.

Jack never mentioned his military experience, but he was drafted by the air force and rose to the eminent position of Lieutenant Major. He was a spotter, his job being to identify key targets and installations behind enemy lines for destruction and elimination. Hazel tells me she did not see him for three years and that this experience completely changed his personality.

Although not well known, Jack was an amateur biblical scholar. In his spare time, he would regularly read the Old and New testaments and could quote scripture by memory and at random.

Rank and privilege were not the same for lack. Rank mean) the acceptance of responsibility and the execution of authority. As for privileges, he did not believe in them. For example, with few exceptions, he traveled air coach on all his foreign missions for UNESCO, although he was entitled to first class. As an extension of this philosophy, he practiced an open-door policy during his 14 years as the top administrator and subsequently Deputy-Director general for UNESCO during which the staff regardless of rank could visit him about personal and professional matters- He is still regarded today by those who remember him, especially by those whom he fondly called "the little staff people" (telephone operators, machinists, drivers, workers etc.) as the quintessential American of good heart, faith, and fairness.

Jack was especially fond and laudatory of people who, like him, felt passionate about their advocacy. Such was the case of the late Barbara Good (a former National Commission staff member) who prepared in the mid-1970s a blockbuster resolution on the promotion of women which required three weeks of advance preparation. Upon adoption by acclamation, Jack left the podium to congratulate Barbara with a handshake and a hug. Shortly thereafter, overcome by joy, emotion, and a sense of fulfillment, she fainted and had to be wheeled off to the UNESCO nursery under Jack's watchful eye.

Another of Jack's great passions was his belief that the wives of senior-ranking UNESCO officials should play a major role in promoting the well-being of the UNESCO family, especially members of delegations from third-world countries. Many of these women found themselves in a large hustling city for the first time. Some had never seen tall buildings or elevators before. And many knew nothing about French customs, practices, idiosyncrasies. And so was born the UNESCO Community Service, coordinated and strengthened by Hazel Fobes. Among its many accomplishments was the publication of a well received booklet by the French media entitled "Practically Yours, Paris and France" (unfortunately now out of print) which greatly contributed to the enrichment of the lives of members of foreign delegations and international civil servants as well. Had it not been for Jack's strong support, the protect might have failed for lack of funding.

Unbeknownst to many, Jack was a prankster extraordinaire. Let me add one other to those mentioned by Dr. Arndt. On Earth Day, which was never officially recognized by UNESCO, Jack asked his personal assistant to go to the market and purchase hundreds of the biggest, juiciest, and reddest radishes she could find and place them on silver trays in the main lobby. His entire staff was then ushered in only to be met by Jack who gave them an up-beat sermonette about Earth Day. Needless to say, the environmental community was thrilled but what amused Jack was how rapidly the radishes disappeared. Anyone who has partaken of this treat will understand what I mean.

In conclusion. what all this suggests to me, ladies and gentlemen, is that Jack, behind that intellectual facade, scholarly mien, and sometimes stern countenance, was at heart a fun-loving guy with bouts of fantasy and whimsicality, a good sense of humor, a sentimentalist who cared deeply about this family and the human race and who, on occasion, liked to let his hair down and engage in self-deprecation and introspection about the frailties of the human condition. Indeed, he was happiest and at peace with himself when dedicating his life to promoting the causes of humanity.

And so, Jack, on behalf of those present, especially those of Americans for UNESCO, we wish you God speed. You were truly a great person and a source of inspiration to many of us. Thank you.

Born and raised in Chicago, John Edwin Fobes graduated cum laude from Northwestern University in 1939, and received his M.S. from Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps from 1942-1946, rising from private to major. After the war, he served in the Secretariat to the United Nations from 1945-1946, during its organizational stages. As a U.S. civil servant in the Bureau of the Budget from 1946-1951, he addressed issues arising from increased multilateral activity immediately following World War II.

He moved to Paris with his family in 1952, where he served for three years as Attaché to the U.S. Delegation to NATO and OEEC, helping to administer the Marshall Plan. On return, he was named director of the State Department's Office of International Administration.

In 1960. the family moved to New Delhi, India, where Dr. Fobes served as assistant director, then deputy director, of the U.S. Mission to India, the largest U.S. foreign-aid program at the time. His ambassador was John Kenneth Galbraith.

In 1964, he returned to Pans, to join UNESCO, the Untied Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization, as Assistant Director-General for Administration. In 1971, he was appointed Deputy Director-General, the organization's chief operating officer, where until his retirement in 1977 he served under two directors: France's René Maheu and Senegal's Amadou Mahtar M'Bow.

Renaming to the U.S., he was named m the US National Commission for UNESCO and elected chairman by the 100-member body. Meanwhile he was working with like-minded colleagues to found the Club of Rome, in which he retained membership from 1978 to 2000.

When the Reagan Administration made its decision to withdraw from UNESCO, Fobes immediately resigned his chairmanship of the U.S. National Commission and retired to Asheville, NC. There he founded Americans for the Universality of UNESCO, an organization of UNESCO-experienced Americans intent upon persuading the U.S. to re-enter the multilateral organization; he kept it alive on family funds, and later with some help from the MacArthur Foundation, for the two decades of U.S. absence from UNESCO. From 1985-2002, he headed AUU; through the organization's network and its Newsletter, he virtually single-handedly kept the idea of UNESCO alive in the American mind. When the U.S. announced re-entry in the Fall of 2002, he passed the leadership of AUU to the next generation, retaining a role as Founder President Emeritus and Chair of its Advisory Council; AUU took a new post re-entry name, Americans for UNESCO (AU), and moved to Washington DC. He was also president of the Western North Carolina Chapter of the United Nations Association and participated vigorously in its programs until the eve of his death.

His honors include: Doctor of humanities (honoris causa), Bucknell University, 1973; the UNESCO Silver Medal for Service, 1983; the UNESCO Nehru Gold Medal in 1992, in recognition of "profound commitment to the Organization and outstanding contribution to the achievement of its goals"; and election as Fellow of the World Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1992.

John Edwin Fobes died at his home at the age of 86 on Jan. 20, 2005. His survivors include his citizen-activist wife of 64 years, Hazel Weaver Fobes; a daughter, Patricia Sanson, of Maryville, TN; a son Jeff Fobes, publisher of the Asheville Mountain Express; three granddaughters; and five great grandchildren.

Read the Tributes to John Fobes by Koïchiro Matsuura and Paul Schafer

Read the Jack Fobes: Lien-Link Memorial Articles by Richard Arndt and Gérard Bolla.