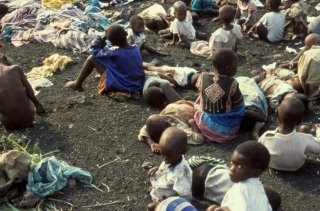

Children in a Congo Refugee Camp

Children in a Congo Refugee CampImage by F. Loock, © UNESCO

Traditionally considered too hot for a global institution to handle, the issue of international migration has recently been moving up the UN agenda. Pierre Sané, Assistant Director-General for Social and Human Sciences (SHS), discusses this issue in the September edition of the SHS Views from the perspective of a complex cross-cutting issue that Social and Human Sciences can address. He emphasizes the contribution of policy-oriented research to human rights-focused understanding and management of social transformations. Without comprehensive intelligence and interventions by the many competent actors, fragmentation, duplication and inefficiency occurs in addressing this issue. The Social and Human Sciences Sector is responsible for implementing the program on international migration. Its aim is to promote respect for migrants’ rights and to contribute to the social integration of migrants. To carry this out, the Sector has five main lines of action:

• Increasing the protection of migrants through participation with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), as well as several NGOs, in an international campaign to encourage States to adhere to the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families;In the September SHS Views issue, articles also examine the issue of International Migration and provide examples of exemplary national efforts.

• Improving national policies of the sending, transit and receiving countries, through promoting research and providing training for policy makers so that there is better management of the impact that migration has on societies;

• Promoting the value of and respect for cultural diversity in multicultural societies and improving the balance between policies that favor diversity and those that favor social integration, by developing initiatives that advocate consideration of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (1992), and the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity;

• Supporting capacity-building, permanence and effectiveness of migrants’ networks as a means of promoting intellectual contribution – as against the current brain drain – through the use of new information and communication technologies; and

• Contributing to the global fight against human trafficking and the exploitation of migrants.

UN Migration Report

In 2005, the International Labour Organization adopted a non-binding Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration. Last year, the independent Global Commission on International Migration presented a report and recommendations to the UN Secretary-General. Secretary-General Kofi Annan proposed a standing forum which governments could use to explore and compare policy approaches. It would make new policy ideas more widely known, add value to existing regional consultations, and encourage an integrated approach to migration and development at both the national and international levels.

This report finds that migration has become a major feature of international life. People living outside their home countries numbered 191 million in 2005 -- 115 million in developed countries, 75 million in the developing world. One third of all current immigrants in the world have moved from one developing country to another, while about the same number have moved from the developing world to the developed. In other words, “South-South” migration is roughly as common as “South-North”. But migration to countries designated as “high-income” – a category which includes some developing countries, such as the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – has grown much faster than to the rest of the world.

Annan pointed out that “the advantages that migration brings are not as well understood as they should be.” Migrants not only take on necessary jobs seen as less desirable by the established residents of host countries, the report finds, but also stimulate demand and improve economic performance overall. They help to shore up pension systems in countries with aging populations.

Throughout human history, migration has been a courageous expression of the individual’s will to overcome adversity and to live a better life. Today, globalization, together with advances in communication and transport, has greatly increased the number of people who have both the desire and the capacity to move.

For their part, developing countries benefit from an estimated $167 billion a year sent home by migrant workers. The exodus of talent from poor countries to more prosperous often poses a severe development loss. But in many countries this is at least partially compensated by migrants’ later return to, and/or investment in, their home countries, where profitable new businesses are established.

“It is for Governments to decide whether more or less migration is desirable,” the Secretary-General says in his introduction to the report. “Our focus in the international community should be on the quality and safety of the migration experience and on what can be done to maximize its development benefits.”“It is time to take a more comprehensive look at the various dimensions of the migration issue, which now involves hundreds of millions of people and affects countries of origin, transit and destination. We need to understand better the causes of international flows of people and their complex interrelationship with development."

Kofi Annan in his report on strengthening the Organization 9/11/2002

There are benefits at both ends of the voyage. The UN report reviews scores of promising policy developments -- multiple-entry visas that provide more fluid and better regulated access to needed immigrant workers, support for immigrant entrepreneurship and host-country training programs, international cooperation to increase training of skilled workers in migrant-sending countries to allay brain drain, and country-of-origin outreach to overseas diasporas.

Migration is not a zero-sum game, the report finds. It can benefit both sending and receiving countries at once. Significantly, many countries once known for emigration – Ireland, the Republic of Korea and Spain among them – now boast thriving economies and host large numbers of immigrants.

The UN report recognizes governments’ right to decide who is allowed to enter their territory, subject to international treaty obligations, as well as their capacity to work together to upgrade economic and social benefits at both ends of the migrant voyage, and to promote the well-being of the migrants themselves. “We find that while countries share people through migration, they often neglect to share knowledge about how to manage the movement of people,” Mr. Annan writes. “We need to learn more systematically from each other.”

HIGH-LEVEL DIALOGUE ON INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT

In September 2006, the General Assembly explored international migration, including most promising aspects: its relationship to development. The potential for migrants to help transform their native countries is capturing the imaginations of national and local authorities, international institutions and the private sector.

In his introductory remarks, Anan pointed out that advancing immigration policy can help meet the UN’s development goals. The scale of migration’s potential for good is huge. To take just the most tangible example, the funds that migrants send back to developing countries—at least $167 billion in 2005 alone—now dwarf all forms of international aid combined.

We have gained many new insights into migration and, especially, into its impact on development. We now understand, better than ever before, that migration is not a zero-sum game. In the best cases, it benefits the receiving country, the country of origin, and migrants themselves. It should be no surprise that countries once associated exclusively with emigration—such as Ireland, the Republic of Korea, Spain, and many others—now boast thriving economies which themselves attract large numbers of migrants. Emigration has played a decisive role in reinvigorating their economies, as has the eventual return of many of their citizens.

International migration is changing as labor markets and society become more global. Those who emigrate no longer separate themselves as thoroughly as they once did from the families and communities they leave behind. No longer do the vast majority settle in just a small number of developed countries: about a third of the world’s nearly 200 million migrants have moved from one developing country to another, while an equal proportion have gone from the developing to the developed world. Nor are migrants engaged only in menial activities. Nearly half the increase in the number of international migrants aged 25 or over in OECD countries during the 1990s was made up of highly skilled people.

Meanwhile, research continues to undermine old assumptions—it shows, for example, that women are somewhat more likely than men to migrate to the developed world, that migrants can maintain transnational lives, and that remittances can dramatically help local economies. At the same time, innovations in policymaking are allowing us to manage international migration in new ways—China and the Republic of Korea attract expatriate researchers back home with state-of-the-art science parks; Governments collaborate with migrant associations abroad to improve livelihoods at home; and development programs help migrant entrepreneurs start small

businesses in their countries of origin.

Owing to the communications and transport revolution, today’s international migrants are, more than ever before, a dynamic human link between cultures, economies and societies. And the wealth of migrants is not measured only in the remittances they send home. Through the skills and know-how they accumulate, they also help to transfer technology and institutional knowledge. They inspire new ways of thinking, both socially and politically. India’s software industry has emerged in large part from intensive networking among expatriates, returning migrants, and Indian entrepreneurs at home and abroad. After working in Greece, Albanians bring home new agricultural skills that enable them to increase production. By promoting the exchange of experience and helping build partnerships, the international community can do much to increase—and spread—these positive effects of migration on development.

Many promising policies are already in place making migration work better for everyone. Some countries are experimenting with more fluid types of migration that afford greater freedom of movement through multiple-entry visas. Others are promoting the entrepreneurial spirit of migrants by easing access to loans and providing management training. Governments are also seeking ways to attract their expatriates’ home: directly, through professional and financial incentives, and indirectly by creating legal and institutional frameworks conducive to return—including dual citizenship and portable pensions. Local authorities, too, are using innovative measures to attract expatriate talent to their cities or regions.

In a closing statement by the president of the 61st session of the General Assembly, H. E. Sheikha Haya Rashed al Khalifa, emphasized the opportunities and challenges that international migration poses for development in each of their countries. He noted that the participants examined the impact of international migration on economic and social development, the centrality of human rights to ensure the development benefits of migration, the importance of remittances, and the crucial role of international cooperation and partnerships to address the challenges posed by international migration. Above all, the forum proven that international migration and development can be debated constructively in the United Nations.

The High-Level Dialogue has affirmed a number of key messages. First, that international migration is a growing phenomenon and is a key component of development in both developing and developed countries. Second, that international migration can be a positive force for development in countries of origin and countries of destination, provided it is supported by the right set of policies. Third, that it is important to strengthen international cooperation on international migration, bilaterally, regionally and globally.

This dialogue has emphasized that respect for human rights is the necessary foundation for the beneficial effects of migration on development to accrue. Some vulnerable groups, such as migrant women and children, need special protection.

Migration is no substitute for development. Too often, migrants are forced to seek employment abroad due to poverty, conflict and the lack of human rights. There has been widespread support for incorporating international migration to the development agenda and for integrating migration issues into national development strategies, including possibly into poverty reduction strategies. There is a need to provide decent work and decent working conditions in countries of origin and countries of destination. This would alleviate the negative aspects of migration including the brain-drain.

Furthermore, remittances are considered one of the most tangible benefits of international migration for development. They improve the lives of millions of migrant families, but also have a positive effect on the economy at large. However, called for are the reduction in the costs of remittances transfers and for maximizing their development potential.

Check out these UNESCO websites:

* International Migration and Multicultural PoliciesSubscribe to UNESCO's Migration and Multicultural Policies Mailing List.

* Migration Research Institutes Database

* Recognition of Qualifications of Migrants

1 comment:

Hello,

Great Podcast! I most certainly wouldn't give up :)

Post a Comment